Allow me to add a small introduction for the benefit of those not familiar with Warhammer 40k and to set the stage even for those familiar with it.

Warhammer 40000 (henceforth just “40k”) is a hobby. I don’t mean that as a joke stating the obvious, I mean that it doesn’t particularly take one singular shape.

It is a fictional setting thriving with novels constantly released about it, it is a tabletop wargame, it is miniature painting, there’s even some videogames. You might only dip into a single one of the elements or you might roll in the mud of all of them.

Regardless of what you choose there’s a very purposeful synergy going on. A novel will make you want miniatures, a cool miniature might make you want to buy a book, one of the videogames might make you wanna check either.

In the tabletop wargame side, the game has seen many iterations with revisions to the rules that range from streamlining to completely different games. And notably, as each edition nears its end and the next one starts, some galaxy-shattering event happens (Or planet-shattering in one specific case).

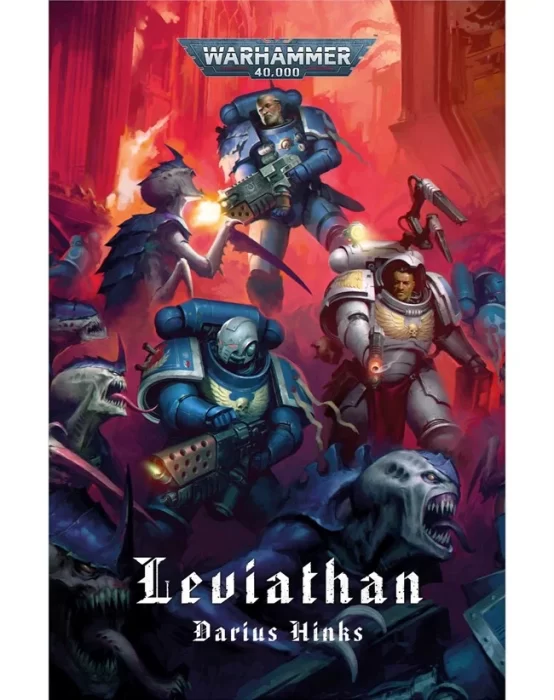

Leviathan is the opening salvo of 10th edition. Both the novel, and the boxed set with the same name.

At first I wondered why the Tyranids of all factions were the ones opening the meta narrative of the new edition. I mean, I love the Tyranids but what makes me love them is also what made them a weird choice.

They’re basically the one antagonist no other faction finds agreeable. A swarm of bugs that just wants to eat and grow to eat more. They don’t have pathos of any kind, they don’t have ethos to follow, and they only possess logos the way a mudslide might follow logic.

Even the ways they subvert and weaken its prey feel like a carefully-evolved venom rather than a conscious action. They can disrupt astropathic communications creating the “shadow in the warp”, this same “shadow” causes nearby populations to sense dread for no reason, resulting in riots and other civil unrest.

They even have at their disposal the existence of the “Gene Stealer Cults” which are… to grossly oversimplify, regular humans that end up carrying (either through infection or birth) mutations that make them more prone to worshipping the Tyranids. With the goal being to cause more civil unrest with the Genstealers disrupting power structures, diverting resources that could be used against the Tyranids. But even this feels deliberate the same way that a flu making you sneeze in order to create an infection vector is deliberate.

They’re fun because even the forces of Chaos, whose machinations befit their name, don’t want them around. But making them the opening threat, especially after the Arks of Omen series of books painted a colorful multi faction conflict sure was… a choice.

And then, I read the book (both the box set one and the novel this article is about). And both of them make the Tyranids the perfect hook for a new edition asking a simple question.

“What if the Tyranids suddenly were more intelligent?”

Or alternatively, and perhaps more harrowingly…

“What if their image as a mindless hive was deliberate all along?”

Like, imagine that you see a wasp nest. Bad, yes, but a predictable thing. Now imagine that a couple of the wasps go your way so you decide to run from them. They’re just wasps, if you outrun them you’ll be safe… and then you realize those two wasps wanted you to run, and with that they routed you head first into a bigger wasp nest.

Leviathan is a very apocalyptic novel, the tone from the very beginning is one of “this world is ending and we need to do something”, and then proceeds to ask what that “something” is.

The narrative shifts between various POVs that feel disconnected (though thematically appropiate) at first. And I’ll be the first to admit that I was wary at first of this narrative device because uh… 40k novels don’t have the best track record about not meandering and/or actually tying the plot points, but to my delight it turns out that they do! Not only do they tie everything but every single point contributes to the end conclusion, both plot-wise and thematically.

All characters wrestle with the question of “what does it matter if everything is going to end?” and the novel seeks to reinforce the idea that “it matters because even then you can fight for a better future in the bigger whole”. This isn’t just in relation to all the sacrifices and struggles that happen, but also in how every single one of the side stories contributes to the ultimate resolution of the book in one way or another.

One thing that the book made me think about, is that a lot of the tonal juggling that 40k has to do involves the fact that nobody is setting out to be “evil”. In the capital D Discourse about fascist overtones and whatnot (that I find silly because if someone has fascist proclivities they’re gonna feel validated by Dora the Explorer if they put enough effort into it, and BY GOD they always will) it’s easy to forget that in the end a big part of the “joke” in 40k is that it’s the system that’s fucked.

I bring this up because this book is a good example of “the road to hell is paved with good intentions”. From how the ruthless daughter of an even more ruthless Hive City governor is genuinely heartbroken about her dad’s deteriorated mental state (from the same psychyc malaise that affects everyone). To one of the main human characters being swayed into authorizing the delivery of fake orders that route the Space Marines to a doomed city, though her intent was to merely delay the Space Marines to make the Liutenant look bad instead of leading them to their slaughter.

The introduction of the book actually sets this mood perfectly. In it Darius Hinks explains how he loves to write the “heroes” of 40k, and how the setting is obsessed with Heroism. And that actually made something click in my head in that matter.

Stories about heroism are always bound to be recontextualized as the opposite in due time. Cowboy serials become the tales of an invading force displacing the natives and dehumanizing them, tales of chivalry become clear propaganda to obfuscate the atrocities that knights commited on the regular, all the 80s action flicks about buff americans kicking other countries asses…

And so, 40k operates on a base level of “yeah, that’s all fucked… what if we keep going for fun though?”. I always saw 40k as the equivalent of a Death Metal album, where obviously nobody in their right mind would go in a shooting spree in the name of Lord Satan, but it’s fun to pretend for a 13 song album that you do, master what you fear, and come out of it most likely wanting to do those dirty deeds even less because at the end of the day it all sounds fucked up doesn’t it? But that dimension about heroism escaped me until this book, it was always there but it’s one of those things that are more obvious once put into words.

Actually, let me go back to that bit I mentioned earlier about the doomed city.

Perhaps the most harrowing thing about this book’s depiction of the Tyranids is the fact that the bugs are learning (or indeed were perhaps aware for a long while) to use tactics other than terror in their psychic assault.

That city blew up because the hive mind managed to hook itself onto a servitor (tl;dr: in 40k AI is forbidden sorta kinda so computers are lobotomized humans) who briefly regained its identity as a human and hungered like the hivemind hungers and in satiating that hunger was convinced to lock all the hive cities vents causing a chain reaction that leveled the whole place.

Elsewhere we also notice small moments of suspicious coordination. That decision to send a squad of Marines to said city? It was the idea of a consul, and who is to say that said consul wasn’t influenced the same way?

This plot point even subverts your expectations if you’re more familiar with the setting. Given everything it’s easy to suspect that those that were affected had Genstealer blood in them, making them more susceptible. And there IS a presence of Genestealer Cults, but there’s also the plot point that the Tyranids have become stronger in affecting others’ brains, including Space Marines that wouldn’t have a drop of Genstealer taint in them. Leaving it ambiguous how much it was just a new power and how much it was the preexisting lore stuff.

Overall, it’s a fun read. And befitting the opening salvo for a new edition, it’s the sort of book that those only getting into 40k will be able to enjoy as much as those already familiar with the material.